This is the first in a series of articles that will explore the magical world of drawing in a browser. The idea is to publish a run of practical micro tutorials - illustrated and in plain english - to make WebGL clear and accessible, and allow anyone to start creating wonders such as this, or this, or this, or this.

What drives me to write this series is that, as I approach WebGL myself, too often I lose my way in a sea of technical terms and foreign concepts (what even is a “shader”?). I spend hours on official and unofficial educational material until, at one point, it clicks. But it could’ve clicked a lot sooner and a lot easier, had the concepts been explained in more basic terms. (By the way, a shader is nothing but a material. With some extra magic. We’ll see more in due time.)

My first post will not actually be a pill, nor micro, but I promise every other post will be published in an easy to digest form. I want to offer you something that can provide you with the basics for understanding a new concept or tool in just a few minutes. But as I said, this first post will be a little bit longer in order to establish a good enough foundation.

Oh, one last thing before we begin. Here is a tentative outline of the structure of the series (I’m sure it will change and adapt as we go on, but it should give you an idea of what to expect):

- Introduction, what is WebGL, what are its potentialities, “Hello Cube”

👆 we are here - What is a “scene”? Let’s build one.

- What is a “shader”? Let’s make one.

- Let’s make some objects with code!

- Let’s make some objects with an external program and import them!

- Let’s play with lights

- Let’s play with materials

- How do I interact with my scene? Mouse and keyboard

- Sound

- React and three.js (react-three-fiber)

- Advanced: let’s build a browser game

- Advanced: let’s build a music visualizer

- Advanced: let’s build a website that lives in 3D space

- Advanced: physics and collisions

Note: a single “chapter” may be spread out into multiple pills.

This is a bit of a long introduction, but I felt it was important to give you the context into which to read this article. And now it’s time to get down to business and talk about what you are here for: WebGL.

WebGL (is not a 3D API)

Didn’t expect this, did you? While there are controversial opinions on the matter, the truth is that WebGL doesn’t provide a lot in terms of 3D out of the box. In fact, 3D is not the primary goal of WebGL, and this is why in your day-to-day work you will probably want to make use of libraries such as OGL, three.js or Babylon. We will cover them later in this article, but let’s get back to WebGL for a moment. If it doesn’t give us 3D tools, what is it that it does?

WebGL draws points, lines and triangles in <canvas> elements using the GPU. That’s it. That’s the tweet. It’s that simple. Ok, it’s not actually that simple, and if you are looking for a rabbit hole feel free to search “GPU vs CPU” and what are the benefits and drawbacks of utilizing the GPU to run programs.

But if there is one piece of information that we should keep from this whole article is that WebGL is a low level library, and you are probably not interested in learning it in depth right now.

A world of possibilities

As you may have seen if you followed the links at the beginning of the article (if not, I recommend doing it now, I’ll be here waiting) WebGL does seem to open up a whole world of possibilities. If you are like me, you will almost feel overwhelmed by the sheer diversity of things you can do with WebGL. Surely learning to do all that must be a ginormous effort, right? And surely you must dedicate hours and hours of research and development day in and day out for months, or even years, before you can build something beautiful, right?

Wrong.

It takes 5 minutes to render a pink spinning cube on the web page of your choice. 2 if it’s the third time you do it. Does it sound more interesting now?

Seriously though, this is what WebGL is for me: possibilities (notice the plural). You can build pretty much anything you want, 2D or 3D, from music players to browser games to fancy hover effects. Sky is the limit, and creativity your friend. We will explore how in a series of simple and non-overwhelming steps over the next few weeks. Or months. We’ll see.

3D libraries

Alright, so. WebGL is an overly complicated low level library, but animating 3D stuff in the browser is supposed to be simple? In a way, yes, thanks to a number of libraries that provide useful abstractions on top of WebGL. The three most popular, ordered by most essential to most complete, are:

In this article we will create a pink spinning cube in all three of them, in order to get a taste of each. But first, how do they compare?

Generally speaking, OGL does its best to be minimal and abstract as little as possible, to the point where you will often have to write native WebGL commands. It does provide a few out-of-the-box shapes and utilities (cube, sphere, fog, shadow…), but not nearly as many as a more complete library such as three.js. It’s a good choice if you aren’t planning on building anything overly complicated, and you’d like to have the perfect excuse to learn a bit more of WebGL.

Three.js is by far the most used 3D library out there. It sometimes has a bad reputation, since the developers tend to “move fast and break things”, so your code might be working with today’s r113 version, but something might break if tomorrow you upgrade to r114. Yes, they do not use semver. Still, due to its ubiquity and popularity, it’s hard to go wrong if you choose it (just look at their examples page). In fact in most of the future 💊 pills I will be using three.js.

Babylon.js is probably the most powerful and complete library of the bunch. While it’s less popular than three.js, it is sponsored (developed?) by Microsoft. It has many features you probably don’t even know are a thing (and neither do I), but most importantly it comes with a set of tools for building games. It would be the library of choice if I had to build something complex, or a browser game.

Hello Cube

I realize I spent a lot of words introducing first this series, and then the world of WebGL. I tried to keep it at a minimum, and we’ll certainly learn a lot more in the following weeks, but now a piece of good news: the time has finally come for the “Hello world” of WebGL 🙌

Please note: the goal of this exercise is to get something done. There will be terms and concepts that may not make much sense yet. I suggest you suspend your curiosity for a moment and try to follow along and put a quick win in your pocket (and maybe show it to your friends). There will be plenty of time to understand everything else as we proceed further along the series!

Setup

I suggest you create, on CodeSandbox, a sandbox for each cube we will make. The code I will show can be pasted in the index.js file provided, and you’ll get an immediate preview on the right side of the screen. For your convenience you can simply open this template: https://codesandbox.io/s/pills-of-webgl-hello-cube-8tft5 and click Fork on the top right.

OGL

Let’s start with the most difficult library :)

First things first: in our newly forked sandbox, click on Add Dependency (you’ll find it on the sidebar), search for ogl and click on it to add it to our project.

Let’s start by initializing the Renderer, which is ultimately responsible for talking to WebGL and drawing pixels on a canvas:

1import {2 Renderer,3 Camera,4 Program,5 Mesh,6 Box,7 Transform8} from 'ogl/dist/ogl.umd.js';910// Initialize the OGL renderer and attach the canvas to our document11const renderer = new Renderer();12const gl = renderer.gl;1314// Append the canvas which will be used by OGL to our document15document.getElementById('app').appendChild(gl.canvas);

Please note: normally it would be enough to write import { ... } from 'ogl';, but due to a bug in CodeSandbox we need to specify that we want the UMD version.

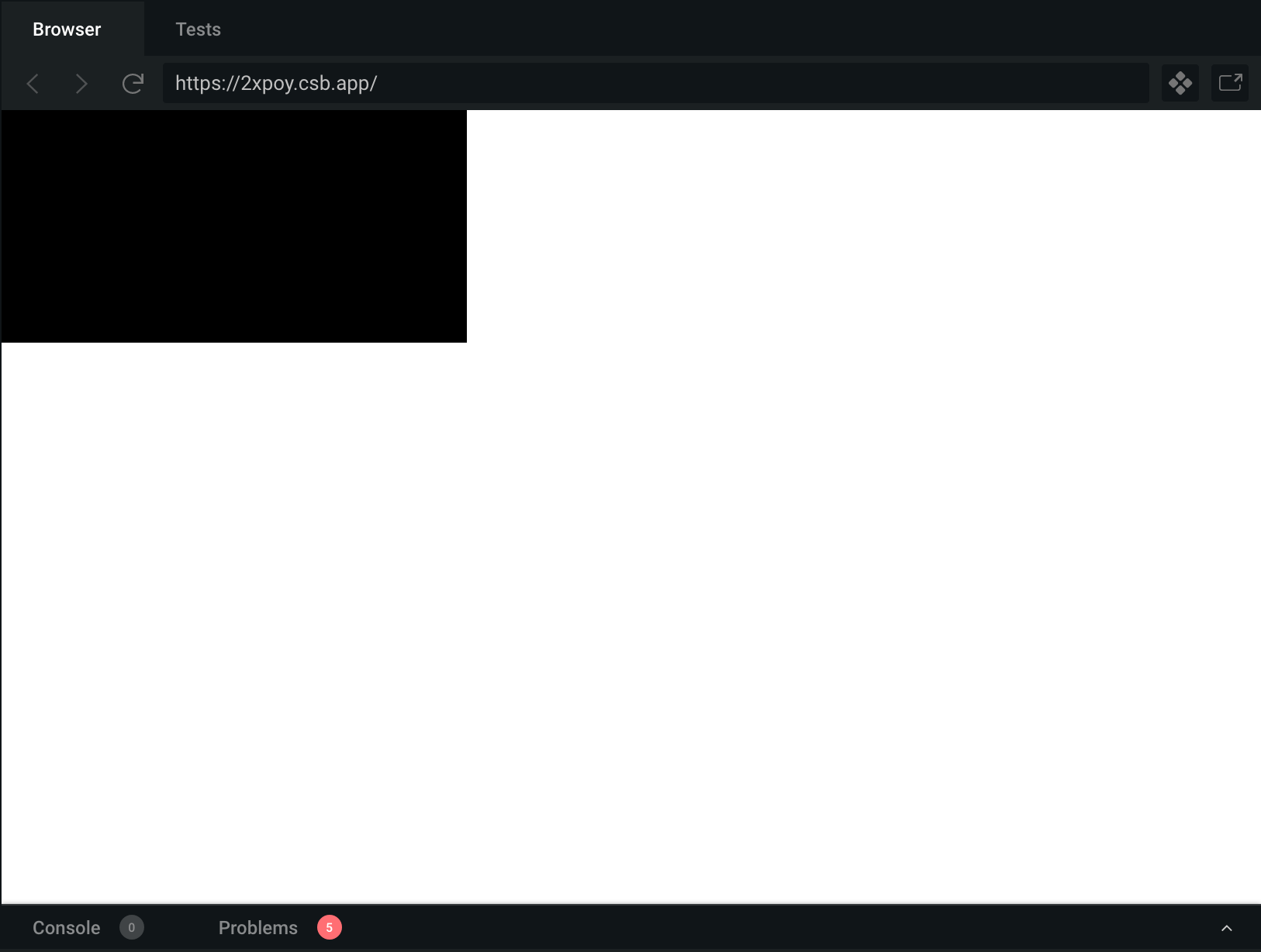

If we glance at the preview we will see a single black rectangle measuring 300x150px. Perfect. That’s the default size of the <canvas> element, and it renders all black because, well, we haven’t done much yet:

Let’s add a Camera. And since we are at it, let’s set the size of our <canvas> to cover the whole page. Add the following code to index.js:

1...23// Append the canvas which will be used by OGL to our document4document.getElementById('app').appendChild(gl.canvas);56// Add a camera7const camera = new Camera(gl);8camera.position.z = 5; // <- this moves the camera "back" 5 units910// Set the size of the canvas11renderer.setSize(window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight);1213// Set the aspect ratio of the camera to the canvas size14camera.perspective({15 aspect: gl.canvas.width / gl.canvas.height16});

Mmm 🤔 the white turned grey, but that 300x150px black box is still there. What gives? That’s ok. We have a renderer who renders in a canvas (if you check the dev tools you’ll see the canvas actually covers the whole window), and we have a camera through which to look at. What’s missing is what the camera should actually look at. Let’s add a Scene, and tell the renderer to render the scene through our camera:

1...23// Set the aspect ratio of the camera to the canvas size4camera.perspective({5 aspect: gl.canvas.width / gl.canvas.height6});78// Add a scene (don't worry about what Transform actually does for the moment)9const scene = new Transform();1011// Draw!12renderer.render({ scene, camera });

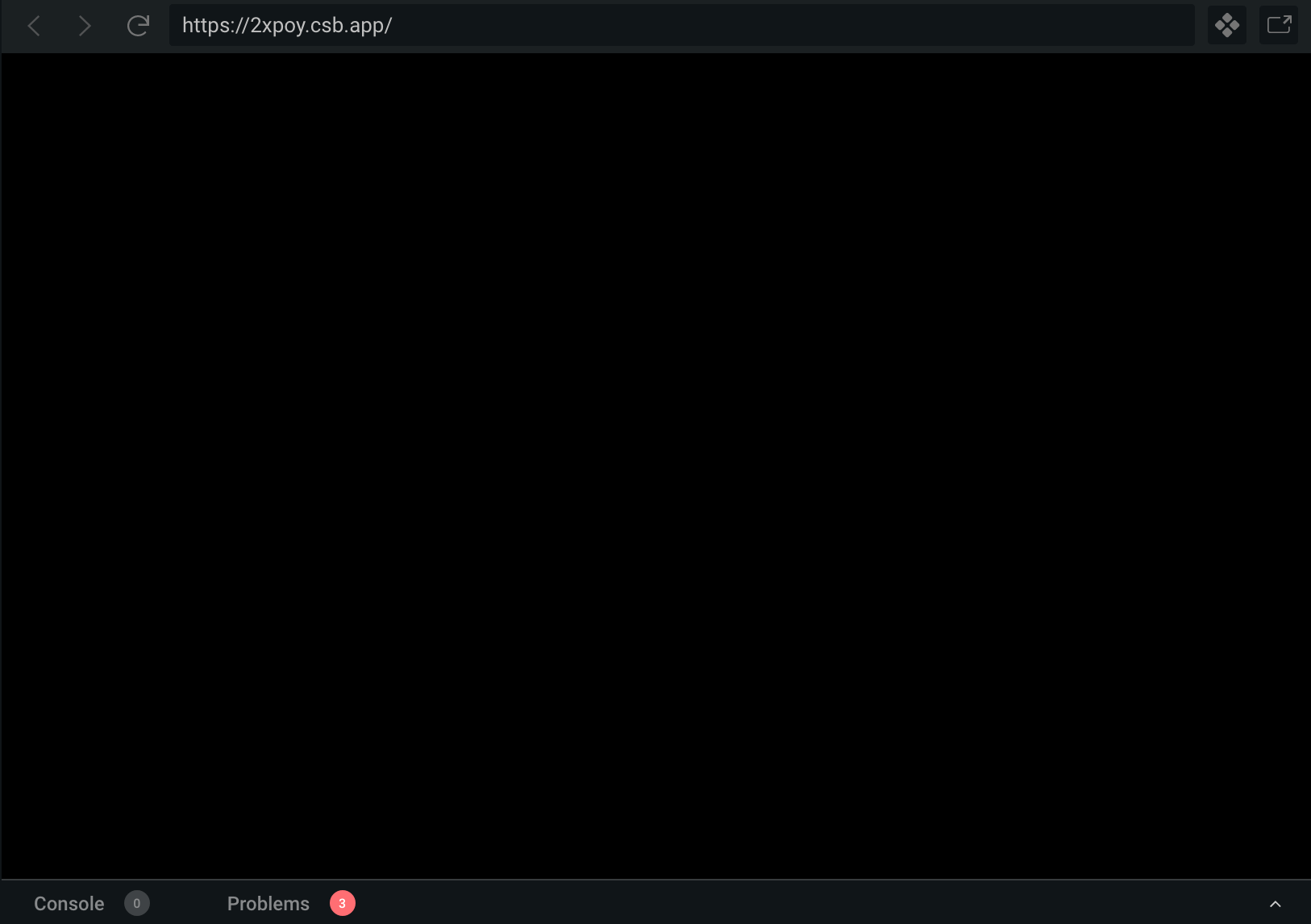

Yay! The whole page is finally black. Good job!

Now we need a Cube. Here things get a little tricky: you will see some stuff, and it will not make much sense, and then you will see similar patterns repeat on the three.js and Babylon.js examples, and then in my next article I will explain what’s actually going on. Just trust the following code for a moment, and add it to your index.js before the draw instruction:

1...23// Add a scene (don't worry about what Transform actually does for the moment)4const scene = new Transform();56// Let's use the Box helper from OGL7const geometry = new Box(gl);89// This complicated set of instructions tells our box to be pink. It's called10// "program" for a reason, but it doesn't matter right now.11const program = new Program(gl, {12 vertex: `13 attribute vec3 position;1415 uniform mat4 modelViewMatrix;16 uniform mat4 projectionMatrix;1718 void main() {19 gl_Position = projectionMatrix * modelViewMatrix * vec4(position, 1.0);20 }21 `,22 fragment: `23 void main() {24 gl_FragColor = vec4(0.92, 0.48, 0.84, 1.0); // Pink!25 }26 `27});2829// Here we say that we want our box (geometry), to be pink (program)30const mesh = new Mesh(gl, { geometry, program });3132// And finally we add it to the scene33mesh.setParent(scene);3435// Draw!36renderer.render({ scene, camera });

Getting there? You should now see a pink square centered in our canvas. It’s actually a cube, but we are looking at it flat front. Let’s give it a spin, shall we?

Add the following lines before renderer.render({ scene, camera });, and hit Save:

1...23// And finally we add it to the scene4mesh.setParent(scene);56// Remember, `mesh` is our pink cube.7// And we can directly mutate some of it's properties!8mesh.rotation.y -= 0.04;9mesh.rotation.x += 0.03;1011// One last thing: MOVE the `draw` instruction that we added earlier down here:12renderer.render({ scene, camera });

Alright I was kidding. That’s definitely not enough to animate our object. We need a little helper, and our little helper is called requestAnimationFrame. Very briefly, requestAnimationFrame is a browser API that allows us to run a function right before the browser repaints the window. If we keep our animation simple enough, the repaint will happen 60 times per second, which is about once every 16ms. This is also known as “buttery smooth”.

Delete the previous two lines and the one reading renderer.render({..., and add the following instead:

1...23// And finally we add it to the scene4mesh.setParent(scene);56// Update the cube spin every 16ms7requestAnimationFrame(update);8function update() {9 requestAnimationFrame(update);1011 mesh.rotation.y -= 0.04;12 mesh.rotation.x += 0.03;13 renderer.render({ scene, camera });14}1516//EOF

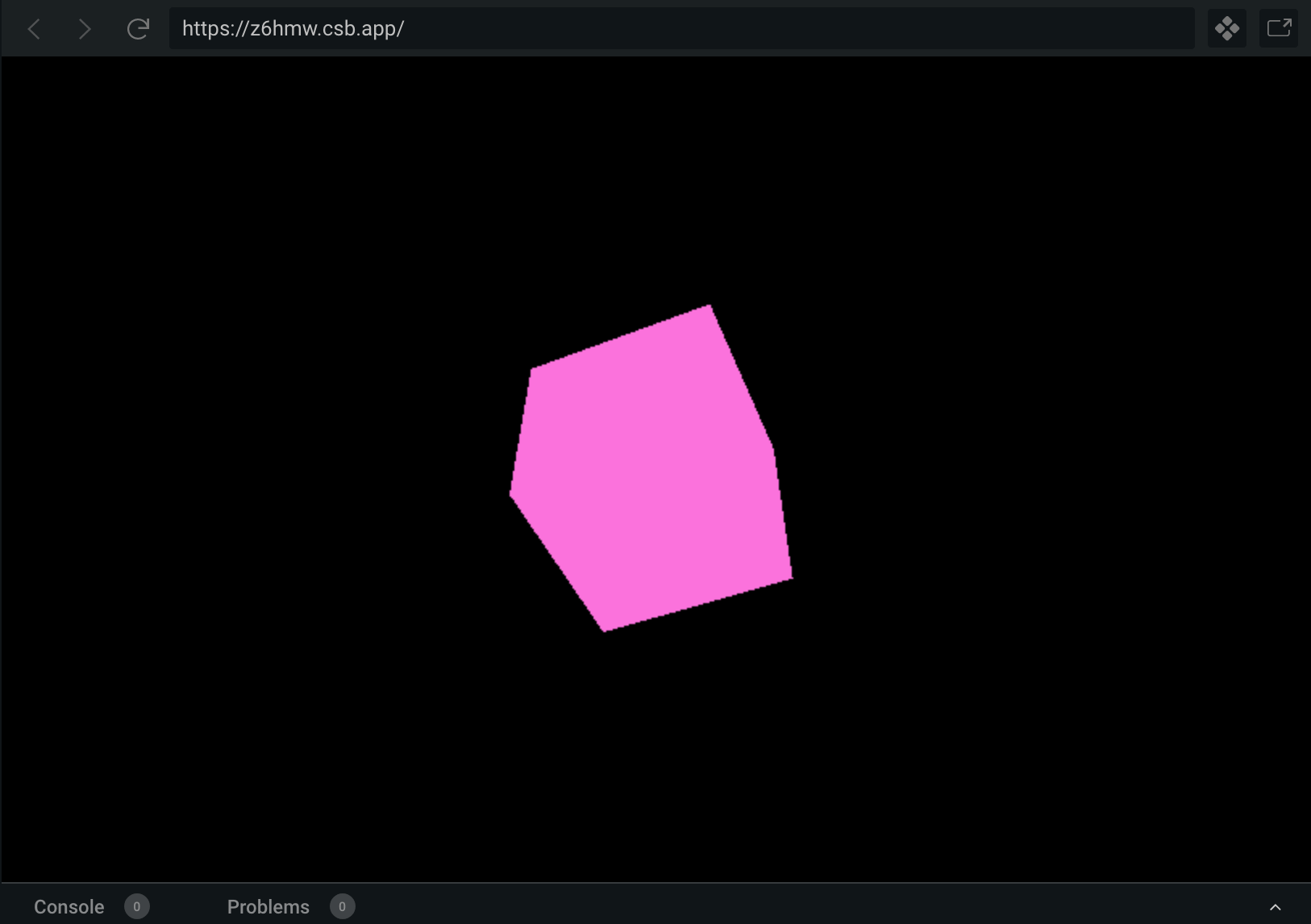

We did it 🥳 Here is the final result:

If your program is not working as intended, click on the “Open Sandbox” button to see the commented source code and compare it with your result!

Exercise for the reader: see if you can give it different colors, spins, and animate it’s position instead.

three.js

I understand this is starting to be a lot to take in, and the article is getting long, but I wanted to build our first Hello Cube step by step in order to dissect all that is needed to animate stuff on our browser. The good news is that that’s it. Everything that will follow from now on will basically be a variation of what we’ve seen so far.

Let’s get our three.js example running and see how they do things instead. This time I’ll skip some steps and we’ll be done before you know it, I promise.

Let’s fork our template https://codesandbox.io/s/pills-of-webgl-hello-cube-8tft5 (again), and this time add the three dependency. Next, let’s set up our scene. Add the following to our index.js:

1import * as THREE from 'three';23// Create our renderer and append the canvas to our document4const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer();5renderer.setSize(window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight);6document.getElementById('app').appendChild(renderer.domElement);78// Add a camera, and move it back 5 units9const FOV = 45; // This corresponds approximately to a 30mm lens10const ASPECT = window.innerWidth / window.innerHeight;11const NEAR = 0.1; // Anything closer than 0.1 units will not be visible12const FAR = 1000; // Anything further than 0.1 units will not be visible13const camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(FOV, ASPECT, NEAR, FAR);14camera.position.z = 5;1516// Make a scene (lol)17const scene = new THREE.Scene();1819// Draw!20renderer.render(scene, camera);

So far nothing new, we are at the “all black” stage. The APIs provided by three.js are a little different, but it’s still mostly english, and we can easily spot a lot of similarities with OGL. Let’s proceed with our Cube:

1...23// Make a scene (lol)4const scene = new THREE.Scene();56// Our helper from three.js7const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry();89// In OGL, this was called `program`. It's the same thing, just easier.10const material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({11 color: 0xea7ad7 // Pink!12});1314// Putting everything together15const cube = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);1617// And finally adding the cube to the scene18scene.add(cube);1920// Draw!21renderer.render(scene, camera);

Remember that lot of confusing lines called program? A program is a shader is a material. Three.js calls it a material, and gives us a bunch of useful presets to start out with, such as MeshBasicMaterial. Let’s animate the cube now:

1...23// And finally adding the cube to the scene4scene.add(cube);56// Update the cube spin every 16ms7requestAnimationFrame(update);8function update() {9 requestAnimationFrame(update);1011 cube.rotation.y -= 0.04;12 cube.rotation.x += 0.03;13 renderer.render(scene, camera);14}1516//EOF

Tadaaa!

All done. But, you know what? Let’s go one tiny step further. I don’t really like that flat look, that’s not what cubes look like, right? Look for the line:

1const material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({

…and change it to:

1const material = new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({

Do you see all black now? Good. We just set our cube to use a physically-based material. This means we now need to add… a Light!

1...23// And finally adding the cube to the scene4scene.add(cube);56// White directional light (by default it looks at the center of the scene)7const directionalLight = new THREE.DirectionalLight(0xffffff, 1);89// Position it to the top left10directionalLight.position.set(-1, 1, 1);1112// Add it to the scene13scene.add(directionalLight);1415// Update the cube spin every 16ms16requestAnimationFrame(update);17function update() {18 requestAnimationFrame(update);1920 cube.rotation.y -= 0.04;21 cube.rotation.x += 0.03;22 renderer.render(scene, camera);23}2425//EOF

Isn’t this a lot better? And with fewer lines of code than in the OGL example.

This is the power of three.js: we have a set of utilities that can make setting up a scene a breeze. Of course, if we wanted we could always opt out of the helpers and apply a custom program/shader to our cube. That’s how some of the coolest stuff is done. But it’s optional and for the moment we have more than we need to get started.

Exercise for the reader: three.js provides a complete set of basic shapes, try to see what else you can spin.

Finally, let’s look at the Babylon.js example.

Babylon.js

As usual, fork our template https://codesandbox.io/s/pills-of-webgl-hello-cube-8tft5 (once again), and this time add the @babylonjs/core dependency (watch out, there is a package called simply babylon which is a parser, NOT the 3D library we are looking for). And let’s set up our scene.

If you remember, in our previous two examples the libraries themselves took charge of creating a <canvas> element, which then we attached to our #app element. Babylon.js instead wants a ready to use canvas, so open index.html and add the following line:

1...23<div id="app">4 <canvas id="renderCanvas" touch-action="none"></canvas>5</div>67...

Going back to index.js, let’s add the usual renderer, camera, and scene, and draw our black rectangle:

1import {2 Engine,3 Scene,4 UniversalCamera,5 MeshBuilder,6 StandardMaterial,7 DirectionalLight,8 Vector3,9 Color3,10} from '@babylonjs/core';1112// Get the canvas element and resize it to cover the full window13const canvas = document.getElementById('renderCanvas');14canvas.width = window.innerWidth;15canvas.height = window.innerHeight;1617// In the previous examples this was called "renderer"18const engine = new Engine(canvas, true);1920// Create the scene21const scene = new Scene(engine);2223// Add a camera called "Camera" 🤓, and move it back 5 units24const camera = new UniversalCamera('Camera', new Vector3(0, 0, 5), scene);2526// Point the camera towards the scene origin27camera.setTarget(Vector3.Zero());2829// And finally attach it to the canvas30camera.attachControl(canvas, true);3132// Draw!33scene.render();

If you hit Save now you’ll see the preview turns purple-ish, and not black. That’s ok, it’s just that Babylon.js likes it less dark than our other friends 🙃. Still, this does not mean that there is a default light illuminating our scene. It’s just sort of the background color of the canvas (not exactly, but it’s a good enough explanation for the moment).

Let’s add our Cube, and Light it up:

1...23// And finally attach it to the canvas4camera.attachControl(canvas, true);56// Create a 1x1 cube (Babylon.js automatically adds it to our scene)7// Note: there is an odler method called simply "Mesh". It is recommended8// to use the newer "MeshBuilder" instead.9const box = MeshBuilder.CreateBox('', {});1011// Make it pink12const pink = new StandardMaterial('Pink', scene);13pink.diffuseColor = new Color3(0.92, 0.48, 0.84);14box.material = pink;1516// And add a light source. Note that it works slightly differently than in17// three.js. The Vector here is not the light's position, but the direction18// it points to.19const light = new DirectionalLight('DirectionalLight', new Vector3(-1, -1, -1), scene);2021// Draw!22scene.render();

You should now see a pink square on a blue background.

As usual, our final step will be to give it a spin! You will notice that this time instead of directly using the requestAnimationFrame browser API, we’ll be calling a couple of utilities provided by Babylon.js.

First, we tell the renderer that before each pass we want to modify the rotation of our cube. Next, we modify our draw instruction to use the engine’s built in loop:

1...23const light = new DirectionalLight('DirectionalLight', new Vector3(-1, -1, -1), scene);45// Our beforeRender function6scene.registerBeforeRender(function() {7 box.rotation.x += 0.03;8 box.rotation.y += 0.04;9});1011// Register a render loop to repeatedly render the scene12engine.runRenderLoop(function() {13 scene.render();14});1516// EOF

Hurray 🙌

Again, if you are stuck somewhere, or are not getting this result, open the sandbox and look through the commented code to spot any differences!

Exercise for the reader: different materials react differently to different lights, explore what else Babylon.js provides.

Conclusions

Well, that’s it for this first installment :)

In this article we went through a few basic concepts, just enough to understand what this WebGL thing is and start getting our hands dirty. We also explored a number of tools that make our life easier when dealing with drawing in the browser. Hopefully seeing differences and similarities in the approaches of these libraries will help you in defining your mental map around WebGL. For example, OGL showed us how to create a material (or program, or shader) writing WebGL instructions (in a next 💊 pill we’ll explore this in more details), and then we saw how three.js and Babylon.js provide their own abstractions.

I hope you enjoyed, and I hope it sparked interest and curiosity on the topic. I also hope my words were approachable, and the hands-on useful and practical. I’d love to hear your comments: you can find me on Twitter (@mjsarfatti, DMs are open) and on dev.to.

If you’d like to be notified of the next article, please do subscribe to my email list. No spam ever, cancel anytime, and never more than one email per week (actually probably much fewer).